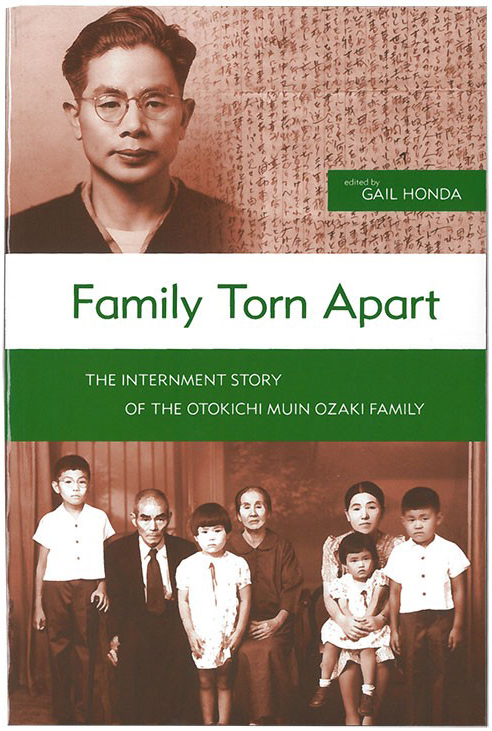

Family Torn Apart: The Internment Story of the Otokichi Muin Ozaki Family (book)

Family Torn Apart is the story of the wartime experiences of Otokichi Muin Ozaki, an Issei who was a Japanese language school teacher, tanka poet, and a leader within the Japanese community in Hilo, Hawai'i. While most incarceration accounts focus on the mainland experience of the English-speaking Nisei who comprised nearly two-thirds of the incarcerated population, Ozaki's story provides insight into the incarceration experience of Hawai'i island Japanese, many of whom authorities detained at mainland incarceration sites. While this book includes radio scripts of Ozaki's incarceration experience and his own accounts of camp news, it is also comprised of letters that family and friends wrote responding to his correspondence. The variety and frequency of these letters and other sources provide intimate details of Ozaki's incarceration that lasted nearly four years. This story highlights the uniqueness of the Hawai'i experience from the perspective of an Issei observer and the impact of incarceration on a family and community.

Otokichi Muin Ozaki was born on November 5, 1904, in Kōchi prefecture on the island of Shikoku in Japan to Tomoya and Shobu Ozaki. His parents immigrated to Hawai'i for a better future and they settled in the Puna district of Hawai'i island. Ozaki arrived in the Islands at age twelve and he completed his education at Hilo Dokuritsu Nihonjin Gakkō. In 1923, he graduated from the eighth grade at 'Ōla'a Grammar School in Puna and attended two years at Hilo High School. Eventually, he taught at Hilo Dokuritsu Nihonjin Gakkō and married Kibei Hideko Kobara. Together they would have four children, Earl Tomoyuki, Alice Sachi, Lily Yuri, and Carl Yukio. After working as a salesman for the Hawaii Mainichi , a daily Japanese newspaper located in Hilo, Ozaki served as an agent for the Japanese Consulate in Hilo helping friends and neighbors process documents. Due to his activism and prominence within the local Japanese community, the FBI and military officials put Ozaki on a list of individuals to be apprehended in Hawai'i in the event of war with Japan. At midnight on December 7, 1941, authorities arrested Ozaki who spent the duration of the war in eight incarceration centers— Kilauea Military Camp on Hawai'i island; Sand Island on O'ahu; Fort McDowell/Angel Island in California; Fort Sill in Oklahoma; Camp Livingston in Louisiana; Santa Fe in New Mexico; Jerome in Arkansas, and Tule Lake in California.

Family Torn Apart is based upon a wide range of materials available at the Resource Center of the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai'i: diary notes, poetry, newspaper articles, correspondence, song lyrics, letters that Ozaki wrote from 1941 to 1943, radio broadcast scripts, and family memorabilia. The collection also includes lists of inmates and records of incarceration centers organizations and operations. The Ozaki family first brought this collection to the Japanese Cultural Center in Hawai'i Resource Center in the late 1990s inquiring about the possibility of archiving his papers that eventually filled over twenty standard archival boxes. It was the first archival collection received by the Resource Center and staff learned about processing and organizing archival collections and preparing finding aids. They were assisted by a grant from the Hawai'i Council for the Humanities to process the material and the Resource Center contracted historical Marie Strazar to write an overview of the collection in the finding aid. Staff members assigned the collection call number "AR1" and bilingual Resource Center volunteers translated the material Ozaki wrote in Japanese. [1]

The main focus of the collection is Ozaki's incarceration experience and the impact of his incarceration upon his family who decided to join him on the mainland after spending the first two years of the war in Hawai'i. The first three chapters describe Ozaki's background, arrest and detention, and finally his removal to mainland incarceration centers. The next four chapters detail the family's struggle to reunite with one another during the war before they are able to return to Hawai'i. After living in a separate center for about a year, Ozaki's family eventually reunited with him in 1944 at Jerome, Arkansas. Throughout his incarceration, Ozaki continuously communicated with his family back in Hawai'i, and the primary goal of the family was to reunite with one another. Interspersed throughout Ozaki's letters are responses from his wife Hideko whose perspective is equally insightful as her life was greatly impacted by her husband's incarceration. As she tried to make the best of this unfamiliar situation, she struggled to maintain the semblance of home and normality. Her letters to her husband include comments about the health and behavior of their children as well as their performance in school. The breadth of Ozaki's correspondence also reveals the network of support that the Ozakis relied upon throughout the war. Many Hawai'i families had sons who enlisted in the army and who were sent to mainland posts. Some of these young men visited Hideko in camp who treated them to home cooked meals. To reciprocate, these families wrote to the Ozakis and sent them gifts revealing a network of support that would span thousands of miles and reflect the close bonds of community in Hawai'i.

Ozaki's account is an exceptional addition to the scholarship on the Japanese American incarceration experience as his narrative is not just an individual account of an Issei from Hawai'i. It also reveals the wartime experiences of other Japanese whose lives were inextricably affected by the war. Although authorities only incarcerated a select number of Hawai'i's Japanese, they often sent these individuals to multiple centers and inmates endured the additional hardship of being separated from their families and communities. Ozaki's account reveals some of the resiliency of the inmates and their families and the bonds of community that transcended distance and separation. As stories like Ozaki's emerge and are disseminated to larger audiences, they add nuance and depth to understandings about the incarceration experience of Japanese and Japanese Americans during World War II.

Footnotes

- ↑ Suzanne Falgout and Linda Nishigaya, "Breaking the Silence: Lesson of Democracy and Social Justice from the World War II Honouliuli Internment and POW Camp in Hawai'i," Social Process in Hawai'i , 45 (2014): 21.

Find in the Digital Library of Japanese American Incarceration

Family Torn Apart: The Internment Story of the Otokichi Muin Ozaki Family

This item has been made freely available in the Digital Library of Japanese American Incarceration , a collaborative project with Internet Archive .

Might also like

Imprisoned Apart: The World War II Correspondence of an Issei Couple

by Louis Fiset;

An Internment Odyssey: Haisho Tenten

by Kumaji Furuya;

Morning Glory, Evening Shadow: Yamato Ichihashi and His Internment Writings, 1942-1945

by Yamato Ichihashi

| Author | Gail Honda (editor) |

|---|---|

| Pages | 279 |

| Publication Date | 2012 |