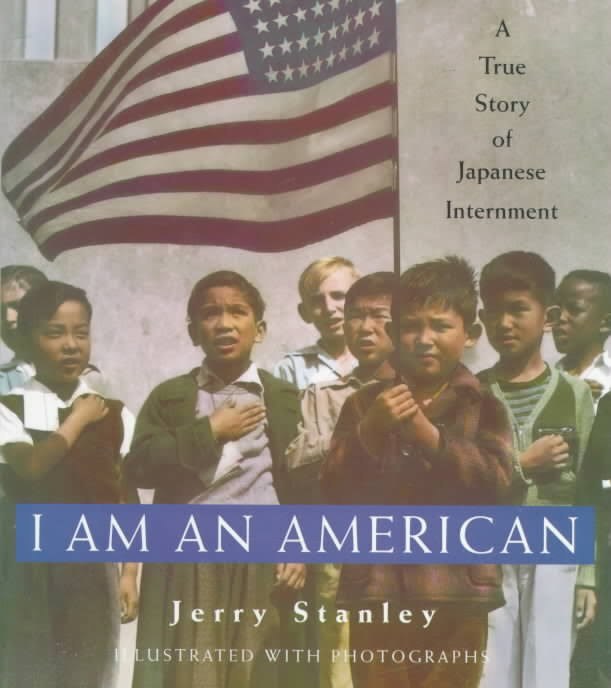

I Am an American: A True Story of Japanese Internment (book)

Creators: Jerry Stanley

Book aimed at middle school audiences that tells the larger story of the Japanese American World War II removal and incarceration through the experiences of one typical Nisei teenager.

Synopsis

The story begins with an introduction of Shiro "Shi" Nomura, eighteen years old and a star athlete at Banning High School in south Los Angeles when the war breaks out. He looks forward to marrying his girlfriend, Amy Hattori, a student of Roosevelt High School in East Los Angeles. However, the Japanese attack changes everything and both of the young people are caught up in the mass forced removal of all West Coast Japanese Americans. After disposing of most of their possessions, Shi and his family end at going to Manzanar, while Amy goes to the Santa Anita Assembly Center.

At Manzanar, Shi recounts the lack of privacy and other elements of concentration camp life. He also is able to sneak out of the camp at night to climb a local hill and look at the stars, while working as a timekeeper. In August 1942, he volunteers to do agricultural labor outside the camp, hoping to get to Colorado to see Amy. He spends two months picking sugar beets in Montana. Though the work is difficult, he enjoys the freedom and he and his friends manage to win over the townspeople. After returning to Manzanar and answering "yes-yes" on the loyalty questionnaire, he gets permission to leave camp for Colorado in May 1943. But when he goes to Amache to propose, she instead breaks up with him. After working in Denver for two months, he decides to return to Manzanar. Back in camp, he works on the camp newspaper, the Manzanar Free Press , plays football and baseball, and is a member of the ManzaKnights, a young men's club. He also meets Mary Kageyama, famous in camp as a singer and they fall in love. The book ends with Shi and Mary's departure from Manzanar in early 1945. An epilogue fills in the intervening years.

Author Jerry Stanley fills in Shi's story with additional information on the incarceration as well as on the exploits of the Nisei in the 100th Infantry Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team, and Military Intelligence Service. (Due to a prior sports injury, Shi is not eligible for military service.) The book includes many large photographs, both from Shi and Mary's personal collection and from governmental sources.

Additional Information

Jerry Stanley (1941– ) is a professional historian specializing in California, western, and Native American history who taught history and California State Bakersfield from 1973 to 1998. A native of Michigan, he entered the Air Force after high school and went on to M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from the University of Arizona. He published his first children's book in 1992 based on prior academic research on school for the children of migrant workers, the acclaimed Children of the Dust Bowl: The True Story of the School at Weedpatch Camp . He got the idea for I Am an American after visiting Manzanar with his wife while on a camping trip. He also visited the Eastern California Museum, where he learned about Shi, who had built much of the museum's holdings on Manzanar.

Though based on a true story, the book has a number of historical errors. The most serious is probably a claim that in 1987, the Supreme Court "finally declared Japanese internment unconstitutional" (pp. 87–88) which did not happen. Stanley also mischaracterizes "voluntary evacuation," noting the "4,000 [who] tried to move, [but] they were met with hostility" (21) without mentioning the 5,000 Japanese Americans who did move out of the restricted area. A map of the restricted area on the same page also leaves out Arizona. Also misleading is the claim that after the "loyalty questionnaire," "all no-no's were sent there [Tule Lake], including 5,700 Nisei—American citizens who had renounced their citizenship" (69; while this is about the right number of Nisei who renounced their American citizenship, nearly all did so after they had been moved to Tule Lake). The author seems to conflate the $38 million paid out under the terms of the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948 with reparations payments authorized by the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 (87). Also erroneous is the claim that "110,723 Japanese were escorted into the assembly centers, while another 6,393 were sent straight to permanent relocation camps" (37–38; about 82,000 went to "assembly centers," while about 28,000 went directly to either Poston (12,000), Manzanar (10,000), Gila River (3,000), or Tule Lake (3,000)). Also repeated is the oft cited but erroneous figure of $400 million as an estimate of property losses by Japanese Americans as a result of their forced removal (84; Japanese American Citizens League leader Mike Masaoka has admitted to making up this figure in testimony before Congress).

Several dates are incorrect: the removal of Japanese American from Terminal Island (January 1942 rather than February; 21); the dates of the 108 Civilian Exclusion Orders ("March, April, and May," though the last ones weren't issued until August 1942; 28–29); the date that the ban on Nisei in the armed forces was lifted (November 1942 rather than February 1943; 64); and the date the recruiters came to the concentration camps seeking volunteers for the army (November and December 1942 rather than March of 1943; 64–65).

Other more minor errors: a claim that the report of the Roberts Commission "even suggested that Japanese farmers had planted their crops in the shape of arrows pointing to Pearl Harbor as the target" (16; the report does not mention Japanese Americans); that the infamous article "How to Tell Your Friends from the Japs" appeared in Time magazine (18; it appeared in Life magazine); that at "Minidoka, in Idaho, the average summer temperature was 110 degrees" (40; the average temperature for July, the hottest month, was 73°); that there were twenty-four barracks in a block at Manzanar (41; there were fourteen); and that Japanese glutinous rice cakes are moche (77, 78; it is mochi ).

Find in the Digital Library of Japanese American Incarceration

I Am an American: A True Story of Japanese Internment

This item has been made freely available in the Digital Library of Japanese American Incarceration , a collaborative project with Internet Archive .

Might also like

Stanley Hayami, Nisei Son

by Joanne Oppenheim;

Fred Korematsu Speaks Up

by Laura Atkins and Stan Yogi;

Thin Wood Walls

by David Patneaude

| Author | Jerry Stanley |

|---|---|

| Pages | 102 |

| Publication Date | 1994 |