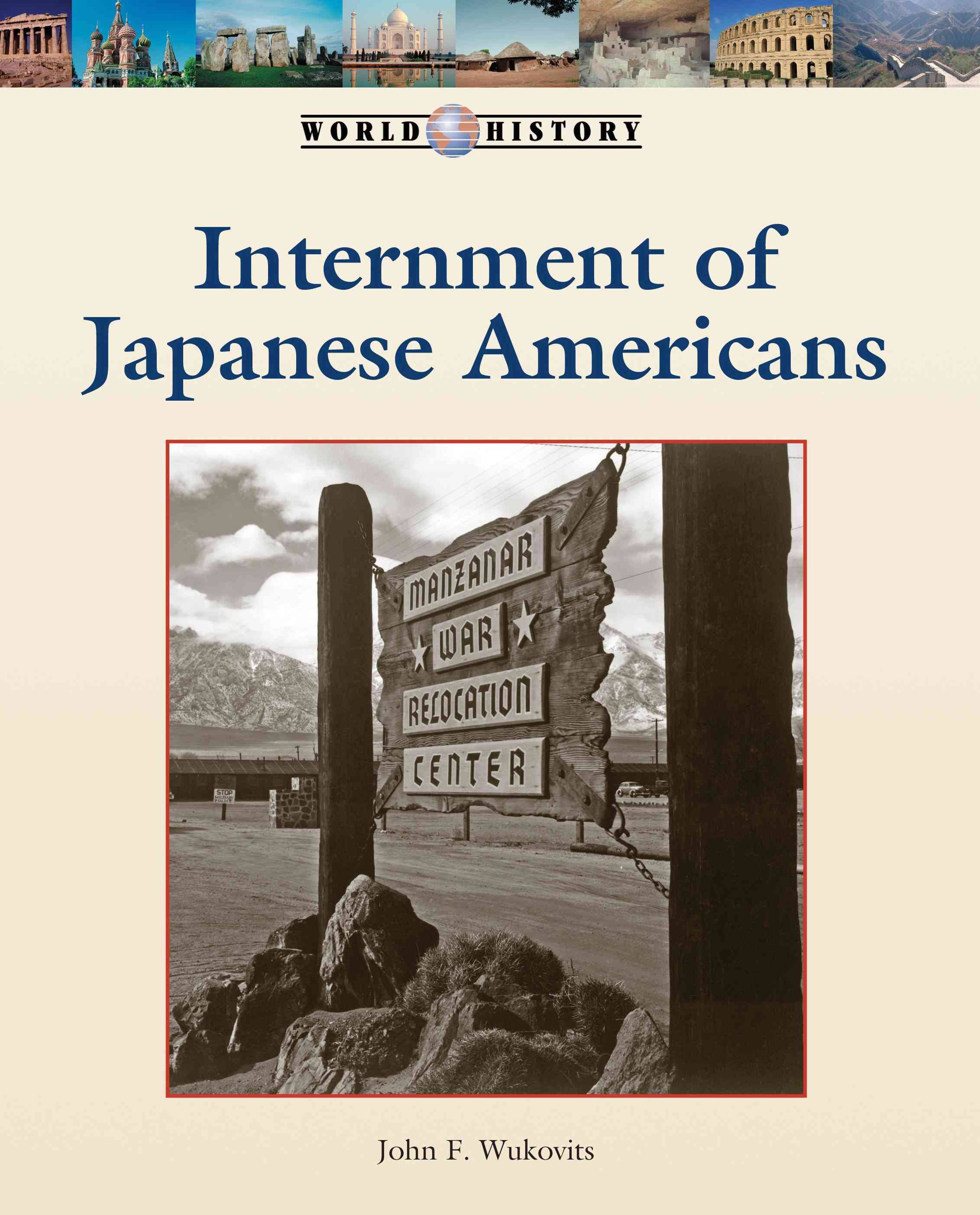

Internment of Japanese Americans (book)

Creators: John F. Wukovits

Non-fiction overview of the Japanese American forced removal and incarceration by John L. Wukovits as part of Lucent Books' World History Series. Published in 2013, the 120-page book is intended for students in grades 7 to 10.

Synopsis

Internment of Japanese Americans consists of six chapters, preceded by a foreword that serves as a general introduction to the "World History Series", an illustrated chronology, and a brief introduction to the topic of Japanese American forced removal and incarceration titled "Altered Lives." Chapter One, "Background to Evacuation," covers Japanese immigration and the anti-Japanese movement, before moving to the attack on Pearl Harbor and its impact on Japanese Americans. Chapter Two, "The Evacuation," briefly covers the chain of events leading up to Executive Order 9066 and provides many details on the subsequent round up of Japanese Americans, drawing heavily on memoirs including those of Mary Tsukamoto and Mary Matsuda Gruenewald. The next two chapters, "Introduction to Camp Life" and "Daily Life in Camp," cover the conditions of life in the " assembly centers " and War Relocation Authority -administered concentration camps, including the physical conditions, the rhythm of daily life, employment, education, sports and recreation, religion, and the impact of camp life on families. Chapter Five, "Protesting the Internment," covers unrest in the camps, the Japanese American court cases, the " loyalty questionnaire ," and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team . The final chapter, "The End of Internment," covers the various ways inmates left the camps, along with brief coverage of the return to the West Coast, the Redress Movement , the coram nobis cases , and the legacy of the incarceration.

The book concludes with a section of Notes and an annotated bibliography. Photographs mostly derived from government sources illustrate the book.

Additional Information

Author John F. Wukovits (1944– ) has published over fifty books since 1995 for both juvenile and adult audiences. A native of Akron, Ohio, he grew up there and the Detroit, Michigan, area and graduated with history degrees from Notre Dame (B.A., 1967) and Michigan State University (M.A., 1968). A junior high school history teacher from 1968 to 2005, Wukovits began writing articles for publication in the 1980s. His juvenile titles are mostly biographies and books on history and sports. He has written biographies on such diverse figures as Anne Frank, Kobe Bryant, Jesse James, and George W. Bush. His adult titles have mostly been in the area of military history, particularly on World War II.

Internment of Japanese Americans includes an unusual number of factual errors. Among them are several proper nouns that are misidentified: General John DeWitt is referred to as "the army commander of the West Coast Defense Command" (page 26; should be "Western Defense Command"); female inmates Haruko Niwa (49) and Chiye Tomihiro (102) are referred to as "he"; Japanese American Citizens League leader Mike Masaoka's name is misspelled as "Masaoke" (81, 85 and in index, 115); Fred Tayama is referred to as "chairman of the Japanese American Citizens League" (76; Tayama held several regional posts with the JACL but was never chairman); The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 is called "The Civil Rights Act of 1988" (101); and the Manzanar National Historic Site is called the "Manzanar State Historic Park" (103).

In a number of cases descriptions of the travails inmates suffered are made too general or are overstated. We are told that Japanese American residents of Bainbridge Island "had twenty-four hours to gather their belongings for an evacuation to an assembly center" (40; they had six days to do so); that barracks were heated by coal stoves (54; in some camps, stoves were fueled by oil or wood); that inmates had to walk "a mile... or more" to use the bathroom or to reach a mess hall (55; there were bathroom and mess facilities located within each block, so walks were far less than a mile); and that "[e]very day began with a siren sounding at 7:00 am" (62; while at least some of the army-run "assembly centers" did have such sirens, there were none in the WRA camps).

Other factual errors: "Between 1860 and 1935, approximately 135,000 Japanese left their homeland to live in the United States...." (13; the number is at least twice as large, perhaps as much as three times as large if one considers Hawai'i to be part of the U.S.); a claim that the 1924 Immigration Act had the effect of "blocking Issei from becoming citizens" (18; the ban on Issei naturalization had been definitively established by the 1922 Ozawa Supreme Court case ); describing the exclusion zones as including "all of California, Oregon, and Washington, and the western half of Arizona" (35; the eastern halves of Oregon and Washington remained free zones, and the restricted part of Arizona is better described as the southern third); a claim that all Japanese Americans had been removed from the West Coast by the end of June (46; removal wasn't completed until mid-August); stating that there were eighteen assembly centers (46; there were fifteen "assembly centers" as well as two "reception centers" that are sometimes counted as "assembly centers"; thus either fifteen or seventeen can be correctly used); a claim that "every camp except Manzanar ... was built simultaneously" (53; Poston , like Manzanar, was first a "reception center," and thus was constructed before the other WRA camps); describing the typical barracks as "[s]tanding 20 feet (6.1m) tall, 100 feet (30m) wide, and 120 feet (37m) long" (53; rather than being almost square, barracks were long and narrow, generally 20 feet wide and 100 or 120 feet long); a claim that "[h]usbands and fathers eventually added minor improvements" to barracks rooms (55; of course women made as many or more improvements to the inmate quarters); describing the orphanage at Manzanar as being run by Maryknoll nuns (72; the Manzanar Children's Village was run by former staff members of the Shonien Home of Los Angeles); a claim that "eighty-five internees refused induction into the military" and that they "received three-year jail terms in federal penitentiaries" (75; there were closer to 300 draft resisters and while some did go to federal prisons, their fates varied widely); a largely inaccurate description of the Manzanar Riot that includes the claim that "a crowd gathered to protest the arrests of Ueno and the individual charged with attacking Tayama" (75; Harry Ueno was himself arrested for attacking Tayama!); a claim that President Franklin D. Roosevelt's oft quoted "Americanism is a matter of mind and heart" statement came from a message he wrote to Secretary of War Henry Stimson (81; the passage was part of the public statement announcing the formation of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and was ghostwritten for the President by WRA Director Dillon Myer and Office of War Information Director Elmer Davis); a claim that "Canada removed from its Pacific coast all Japanese male aliens aged eighteen to sixty-five and placed them in work camps" (82; while not untrue, this was just a part of the mass removal of Japanese Canadians); a claim that "the WRA transferred 6,538 people out of Tule Lake ... and into Heart Mountain " (84; while that number did get transferred out of Tule Lake in the process of segregating the "disloyal," they were transferred to several of the other camps, not just Heart Mountain); describing the Japanese American military units as "the 442nd Regimental Combat Team from the mainland and the 100th Battalion from Hawaii" (85; the 442nd was comprised of roughly equal numbers of Hawai'i and mainland Nisei ; while the original members of the 100th were all from Hawaii, many later replacements came from the continental U.S.); cites the 442nd as having received two Medals of Honor (87–88; members of the 442nd and 100th received 21 Medals of Honor); a claim that "[p]ayments [for redress] were also sent out to the heirs of any former internees who had died before the bill became law" (101; only those former inmates alive when the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was signed into law were eligible for reparations).

Might also like The Invisible Thread by Yoshiko Uchida; A Fence Away from Freedom: Japanese Americans and World War II by Ellen Levine; Dear Miss Breed: True Stories of the Japanese American Incarceration During World War II and a Librarian Who Made a Difference by Joanne Oppenheim

| Author | John F. Wukovits |

|---|---|

| Pages | 120 |

| Publication Date | 2013 |