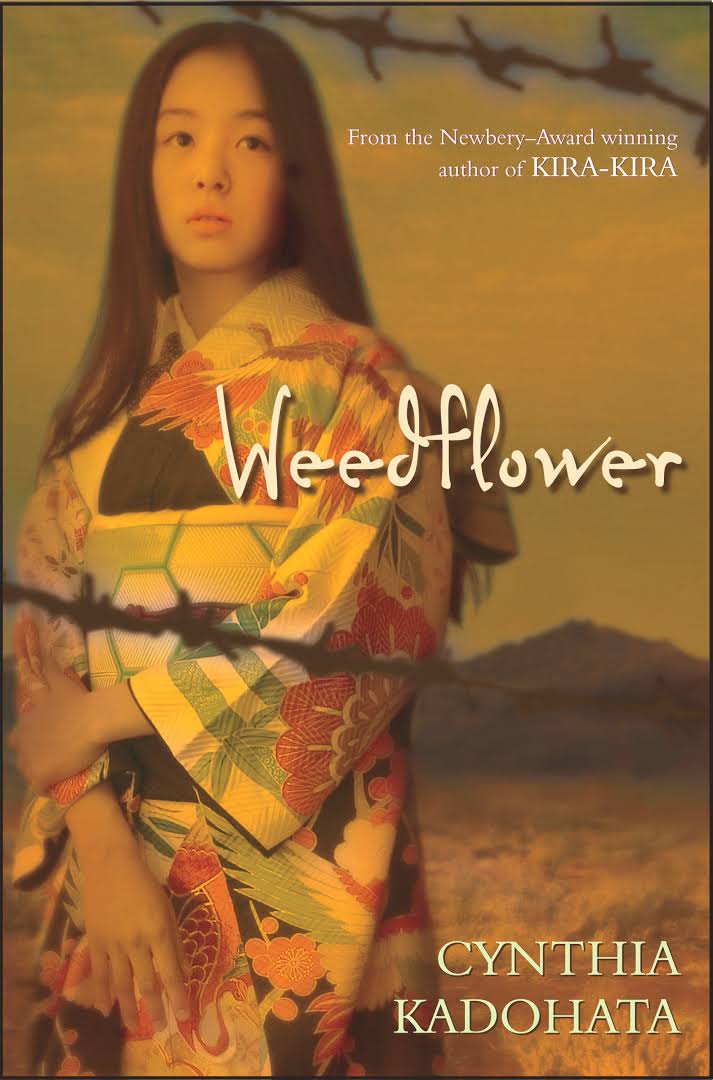

Weedflower (book)

Coming-of-age novel for young adults set in Poston with a young Nisei girl as the protagonist. Weedflower was author Cynthia Kadohata's second young adult novel, after the Newbery Medal winning Kira-Kira .

As the novel begins, Sumiko Matsuda is in the sixth grade. She and her almost six-year-old brother Tak-Tak had been orphaned years ago when their parents were killed in a car accident. They now live with an aunt and uncle, two adult cousins, and a grandfather who run a flower farm in California. She enjoys the farming life and dreams of owning her own flower shop one day. Excited about being invited to a birthday party thrown by a white classmate, she is devastated when the classmate's mother dis-invites her at door when she finds out she is Japanese. The attack on Pearl Harbor the next morning compounds her problems. Initially taken to "San Carlos Racetrack" (seemingly modeled on Santa Anita Assembly Center ) where they live in a horse stall, they eventually end up at Poston. Eventually, she befriends a neighbor man and they build an award winning garden together outside their barracks. Sumiko also meets a Native American boy named Frank. Their uneasy relationship that moves from misunderstanding and distrust on the one hand to general friendship with even a hint of romance on the other, mirrors that of relations between the two groups as a whole. But the loyalty questionnaire stirs up unrest at the camp and within her family, leading to difficult decisions as to their futures. The book's title comes from a Japanese term for flowers grown in the field, as opposed to in a greenhouse; it becomes Frank's nickname for Sumiko.

Author Kadohata was born in Chicago in 1956 and had an itinerant childhood. After his release from Poston, her Nisei father worked as a chick sexer—a popular occupational niche for Japanese Americans that involved quickly determining the sex of baby chicks—which brought the family to Arkansas when Cynthia was around two. Her parents divorced when she was about nine and she moved with her mother, sister and brother to Michigan, then back to Chicago, then to Los Angeles, where she attended high school and went on to the University of Southern California, where she graduated in 1977. Her big break as a writer came with the sale of a story to the New Yorker in 1986; along with other short stories, it became the basis for her debut novel, The Floating World , published in 1989 to great acclaim. Given her focus on young woman protagonists, an editor friend convinced her to try writing a book for young adults. Kira Kira , published in 2004, also won great acclaim and was awarded the Newbery Medal in 2005. [1]

In June 2004, Kadohata went to Kazakhstan to adopt a son, but ended up stuck in the bureaucracy there for several months. She wrote much of what would become Weedflower in Kazakhstan. She told interviewer Alleen Nilsen that she came up with the concept of the "ultimate boredom"—a key element in the book—due to her experience in Kazakhstan. "This was a good lesson to me about the importance of living a character's emotions," she recalled. "When writing historical novels, there is no way that I can relive the actual historical events; but now I am encouraged to realize that in totally different times and in totally different parts of the world I can relive some of the emotions, and then I can do research to find out the details." [2]

Reviews of Weedflower were almost uniformly positive with reviewers noting in particular the appealing heroine, the interactions between Sumiko and Frank, and the "ultimate boredom" concept for praise.

Footnotes

- ↑ "Kadonata, Cynthia, 1956–," Something about the Author: Facts and Pictures about Authors and Illustrators of Books for Young People , Vol. 273 (Farmington Hills, Mich.: Gale, Cengage Learning), 2015), 70–74; Lisa See, "PW Interviews: Cynthia Kadohata," Publishers Weekly , Aug. 3, 1992, 48–49; Hsiu-chuan Lee, "Interview with Cynthia Kadohata," MELUS 32.2 (Summer 2007): 165–86; Caitlyn M. Dlouhy, "Cynthia Kadohata," Horn Book Magazine , July-August 2005, 419–27.

- ↑ Alleen Nilsen, "Interview with Cynthia Kadohata," June 10, 2006 at Children's Literature Association meeting, Manhattan Beach, CA, Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 50.4 (Dec. 2006), 313.

Find in the Digital Library of Japanese American Incarceration

This item has been made freely available in the Digital Library of Japanese American Incarceration , a collaborative project with Internet Archive .

| Author | Cynthia Kadohata |

|---|---|

| Pages | 260 |

| Publication Date | 2006 |

| Awards | Jane Addams Children's Book Award for Older Readers, 2007 |

For More Information

Publisher's website: http://books.simonandschuster.com/Weedflower/Cynthia-Kadohata/9781416975663 .

"Kadohata, Cynthia, 1956–. Something about the Author: Facts and Pictures about Authors and Illustrators of Books for Young People , Vol. 273. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Gale, Cengage Learning, 2015. 70–74.

Lai, Paul. "Militarized Friendship Narratives: Enemy Aliens and Indigenous Outsiders in Cynthia Kadohata's Weedflower." College Literature 41.1 (Winter 2014): 66–89.

Reviews

Brabander, Jennifer M. Hornbook Magazine 82.4 (July-Aug. 2006): 443–44. ["Kadohata again creates a sympathetic, believable young protagonist and a vividly realized setting."]

Bush, Elizabeth. Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books 59.10 (June 2006): 458–59. ["Although other novels have taken on the theme of Japanese-American internment, Kadohata explores not only the activities of the camp but also the inactivity, called by Sumiko 'the ultimate boredom,' which often leaves her lethargic, querulous, and frightened at her own lack of motivation."]

Capehart, Tim. VOYA 28.6 (Feb. 2006): 487–88. ["In this important book from a noted author, the subject matter is slightly marred by inconsistent and flat characterizations and a narrative tendency to tell rather than to show, as well as an overabundance of exclamation points."]

"Focus on Kids' & YA Lit," Kirkus Reviews , Feb. 15, 2006, Spring & Summer Preview, 20.

Kirkus Reviews , Mar. 15, 2006, 293. ["Like weedflowers, hope survives in this quietly powerful story."]

Nilsen, Alleen Pace. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 50.4 (Dec. 2006): 310–11. ["... leaves readers feeling close to a girl they would like to know better."]

Odean, Kathleen. "Bookmarkit." Teacher Librarian 34.2 (Dec. 2006): 10. ["This absorbing novel brings the camp, with its deprivations and its displays of courage, vividly to life."]

Publishers Weekly , Feb. 27, 2006, 62. ["Kadohata clearly and eloquently conveys her heroine's mixture of shame, anger and courage. Readers will be inspired by Sumiko's determination to survive and flourish in a harsh, unjust environment."]

Rochman, Hazel. Booklist , Apr. 15, 2006, 59. ["… the research never swamps the story thanks to the beautifully individualized characters."]

Russell, Mary Harris. "For Young Readers." Chicago Tribune Books, Apr. 9, 2006, 7. ["... Sumiko isn't a stick figure posed in front of historical data. She's a young woman we understand, struggling to survive emotionally."]

School Librarian 55.1 (Spring 2007): 46.

School Library Monthly 27.2 (Nov. 2010): 28.

Sinofski, Esther. 'Library Media Connection 25.4 (Jan. 2007): 74. ["... this historical fiction title is excellent for discussions of family, friendships, and prejudice."]

Sychterz, Terre. Childhood Education 83.5 (Annual 2007): 327.

Taniguchi, Marilyn. School Library Journal 52.7 (July 2006): 106. ["The concise yet lyrical prose conveys her story in a compelling narrative that will resonate with a wide audience."

Wood, Sarah A. Teenreads , Apr. 1, 2006. ["The power of Weedflower is in Kadohata's clarity of detail and her deeply personal approach to the material."]